Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how our minds actually affect our bodies, 7 life-learnings from 7 years of Brain Pickings illustrated, Malcolm Gladwell on criticism and changing your mind, Bill Hicks on what freedom of speech really means, how to live with presence and break the tyranny of productivity, and more. – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how our minds actually affect our bodies, 7 life-learnings from 7 years of Brain Pickings illustrated, Malcolm Gladwell on criticism and changing your mind, Bill Hicks on what freedom of speech really means, how to live with presence and break the tyranny of productivity, and more. – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

"The moral challenge and the grim problem we face," Alan Watts argued in his superb 1970 essay on the difference between money and wealth, "is that the life of affluence and pleasure requires exact discipline and high imagination." Hardly anywhere is this urgency manifested more vibrantly than in startup culture. So argues English programmer and writer Paul Graham – who went to art school studying painting after finishing grad school in computer science, and whose timelessly wonderful meditation on prestige vs. purpose remains a must-read – in an essay titled "How to Make Wealth," found in the 2004 anthology Hackers & Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer Age (public library). Echoing Watts, Graham defines a startup as "a way to compress your whole working life into a few years" and begins his exploration of "how to make money by creating wealth and getting paid for it" with an essential distinction between the two:

"The moral challenge and the grim problem we face," Alan Watts argued in his superb 1970 essay on the difference between money and wealth, "is that the life of affluence and pleasure requires exact discipline and high imagination." Hardly anywhere is this urgency manifested more vibrantly than in startup culture. So argues English programmer and writer Paul Graham – who went to art school studying painting after finishing grad school in computer science, and whose timelessly wonderful meditation on prestige vs. purpose remains a must-read – in an essay titled "How to Make Wealth," found in the 2004 anthology Hackers & Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer Age (public library). Echoing Watts, Graham defines a startup as "a way to compress your whole working life into a few years" and begins his exploration of "how to make money by creating wealth and getting paid for it" with an essential distinction between the two:

If you want to create wealth, it will help to understand what it is. Wealth is not the same thing as money. Wealth is as old as human history. Far older, in fact; ants have wealth. Money is a comparatively recent invention.

If you want to create wealth, it will help to understand what it is. Wealth is not the same thing as money. Wealth is as old as human history. Far older, in fact; ants have wealth. Money is a comparatively recent invention.

Wealth is the fundamental thing. Wealth is stuff we want: food, clothes, houses, cars, gadgets, travel to interesting places, and so on. You can have wealth without having money. If you had a magic machine that could on command make you a car or cook you dinner or do your laundry, or do anything else you wanted, you wouldn't need money. Whereas if you were in the middle of Antarctica, where there is nothing to buy, it wouldn't matter how much money you had.

Wealth is what you want, not money. But if wealth is the important thing, why does everyone talk about making money? It is a kind of shorthand: money is a way of moving wealth, and in practice they are usually interchangeable. But they are not the same thing, and unless you plan to get rich by counterfeiting, talking about making money can make it harder to understand how to make money.

Money is a side effect of specialization. In a specialized society, most of the things you need, you can't make for yourself. If you want a potato or a pencil or a place to live, you have to get it from someone else.

Illustration from Henry Builds a Cabin, a children's book about Thoreau's philosophy

Unlike Buckminster Fuller, who saw specialization as a social evil, Graham considers it the natural progression of an exponentially advancing society. It first gave rise to trade between specialized forms of wealth (e.g., my homegrown tomatoes for your carpentry), then eventually sparked the creation of an intermediate stage – money (my tomatoes for a shilling, a shilling for your carpentry). Somewhere along the way, Graham argues, we lost sight of the fact that money is just an intermediary. He writes:

People think that what a business does is make money. But money is just the intermediate stage – just a shorthand – for whatever people want. What most businesses really do is make wealth. They do something people want.

People think that what a business does is make money. But money is just the intermediate stage – just a shorthand – for whatever people want. What most businesses really do is make wealth. They do something people want.

From this, in turn, stems one of the most toxic fallacies we subscribe to – something legendary graphic designer Milton Glaser so eloquently debunked in considering the manifestable kindness of the universe. Graham writes of "the pie fallacy":

A surprising number of people retain from childhood the idea that there is a fixed amount of wealth in the world. There is, in any normal family, a fixed amount of money at any moment. But that's not the same thing. When wealth is talked about in this context, it is often described as a pie. "You can't make the pie larger," say politicians…

A surprising number of people retain from childhood the idea that there is a fixed amount of wealth in the world. There is, in any normal family, a fixed amount of money at any moment. But that's not the same thing. When wealth is talked about in this context, it is often described as a pie. "You can't make the pie larger," say politicians…

What leads people astray here is the abstraction of money. Money is not wealth. It's just something we use to move wealth around. So although there may be, in certain specific moments (like your family, this month) a fixed amount of money available to trade with other people for things you want, there is not a fixed amount of wealth in the world. You can make more wealth. Wealth has been getting created and destroyed (but on balance, created) for all of human history.

Illustration from How People Earn and Use Money

What's more, Graham points out, the relationship between wealth and money isn't always a linearly transactional one:

Wealth can be created without being sold. Scientists, till recently at least, effectively donated the wealth they created. We are all richer for knowing about penicillin, because we're less likely to die from infections. Wealth is whatever people want, and not dying is certainly something we want.

Wealth can be created without being sold. Scientists, till recently at least, effectively donated the wealth they created. We are all richer for knowing about penicillin, because we're less likely to die from infections. Wealth is whatever people want, and not dying is certainly something we want.

But this is where Graham loses me a bit: The way to make wealth, he argues, is "to start doing something people want." And yet this falls closer to on-demand manufacturing than the kind of wealth-creation that happens when people are presented with something they didn't yet know they wanted. Buzzfeed gives people what they want – most frequently, what their lowest selves want. Buzzfeed is making money. But is Buzzfeed creating cultural wealth? After seven years of Brain Pickings, I side even more wholeheartedly with E.B. White and believe what he once said of journalism – that the role of the writer is "to lift people up, not lower them down" – applies equally to every field of cultural endeavor. To create wealth is not to give people what they want, but to help them figure out what to want by making sense of what is worth having. There is a moral element to the marketable deliverable.

Graham takes this point in an even more worrisome direction in a footnote, where he writes:

There are many senses of the word "wealth," not all of them material. I'm not trying to make a deep philosophical point here about which is the true kind. I'm writing about one specific, rather technical sense of the word "wealth." What people will give you money for. This is an interesting sort of wealth to study, because it is the kind that prevents you from starving. And what people will give you money for depends on them, not you. When you're starting a business, it's easy to slide into thinking that customers want what you do. During the Internet Bubble I talked to a woman who, because she liked the outdoors, was starting an "outdoor portal." You know what kind of business you should start if you like the outdoors? One to recover data from crashed hard disks. What's the connection? None at all. Which is precisely my point. If you want to create wealth (in the narrow technical sense of not starving) then you should be especially skeptical about any plan that centers on things you like doing.

There are many senses of the word "wealth," not all of them material. I'm not trying to make a deep philosophical point here about which is the true kind. I'm writing about one specific, rather technical sense of the word "wealth." What people will give you money for. This is an interesting sort of wealth to study, because it is the kind that prevents you from starving. And what people will give you money for depends on them, not you. When you're starting a business, it's easy to slide into thinking that customers want what you do. During the Internet Bubble I talked to a woman who, because she liked the outdoors, was starting an "outdoor portal." You know what kind of business you should start if you like the outdoors? One to recover data from crashed hard disks. What's the connection? None at all. Which is precisely my point. If you want to create wealth (in the narrow technical sense of not starving) then you should be especially skeptical about any plan that centers on things you like doing.

What a heartbreaking proposition. If we didn't invest so much of ourselves in what we do – which includes what we ourselves believe, what we wish existed, and what direction we want to move the world in – then why bother doing it at all? As John Green put it, it's about making gifts for people and putting them into the world, hoping those gifts might bring them joy and eventually bring us some form of "wealth," but not putting them into the world because they will bring us wealth and with the primary aim that they do so.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from I'll Be You and You Be Me by Ruth Krauss

And yet, though Graham himself might confuse money with wealth at times, he does offer excellent insight into the advantages of startups – of being "part of a small group working on a hard problem" – over traditional companies. He writes:

A big company is like a giant galley driven by a thousand rowers. Two things keep the speed of the galley down. One is that individual rowers don't see any result from working harder. The other is that, in a group of a thousand people, the average rower is likely to be pretty average.

A big company is like a giant galley driven by a thousand rowers. Two things keep the speed of the galley down. One is that individual rowers don't see any result from working harder. The other is that, in a group of a thousand people, the average rower is likely to be pretty average.

If you took ten people at random out of the big galley and put them in a boat by themselves, they could probably go faster. They would have both carrot and stick to motivate them. An energetic rower would be encouraged by the thought that he could have a visible effect on the speed of the boat. And if someone was lazy, the others would be more likely to notice and complain.

But the real advantage of the ten-man boat shows when you take the ten best rowers out of the big galley and put them in a boat together. They will have all the extra motivation that comes from being in a small group. But more importantly, by selecting that small a group you can get the best rowers. Each one will be in the top 1%. It's a much better deal for them to average their work together with a small group of their peers than to average it with everyone.

(It's worth pausing here to note that the carrots-and-sticks method isn't really what motivates us – a trifecta sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose is. Even in Graham's boat analogy, this is likely the underlying force propelling the rowers.)

Graham continues:

That's the real point of startups. Ideally, you are getting together with a group of other people who also want to work a lot harder, and get paid a lot more, than they would in a big company. And because startups tend to get founded by self-selecting groups of ambitious people who already know one another (at least by reputation), the level of measurement is more precise than you get from smallness alone. A startup is not merely ten people, but ten people like you.

That's the real point of startups. Ideally, you are getting together with a group of other people who also want to work a lot harder, and get paid a lot more, than they would in a big company. And because startups tend to get founded by self-selecting groups of ambitious people who already know one another (at least by reputation), the level of measurement is more precise than you get from smallness alone. A startup is not merely ten people, but ten people like you.

He concludes with a piece of advice, both practical and philosophical, on how to choose the direction in which the energetic rowers steer the boat. In a sentiment that parallels Steven Pressfield's assertion that "the more scared we are of a work or calling, the more sure we can be that we have to do it," Graham urges:

Use difficulty as a guide not just in selecting the overall aim of your company, but also at decision points along the way… Suppose you are a little, nimble guy being chased by a big, fat, bully. You open a door and find yourself in a staircase. Do you go up or down? I say up. The bully can probably run downstairs as fast as you can. Going upstairs his bulk will be more of a disadvantage. Running upstairs is hard for you but even harder for him.

Use difficulty as a guide not just in selecting the overall aim of your company, but also at decision points along the way… Suppose you are a little, nimble guy being chased by a big, fat, bully. You open a door and find yourself in a staircase. Do you go up or down? I say up. The bully can probably run downstairs as fast as you can. Going upstairs his bulk will be more of a disadvantage. Running upstairs is hard for you but even harder for him.

All the essays in Hackers & Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer Age make for a provocative read. Complement it with Anna Deavere Smith on discipline and how to stop letting others define us.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

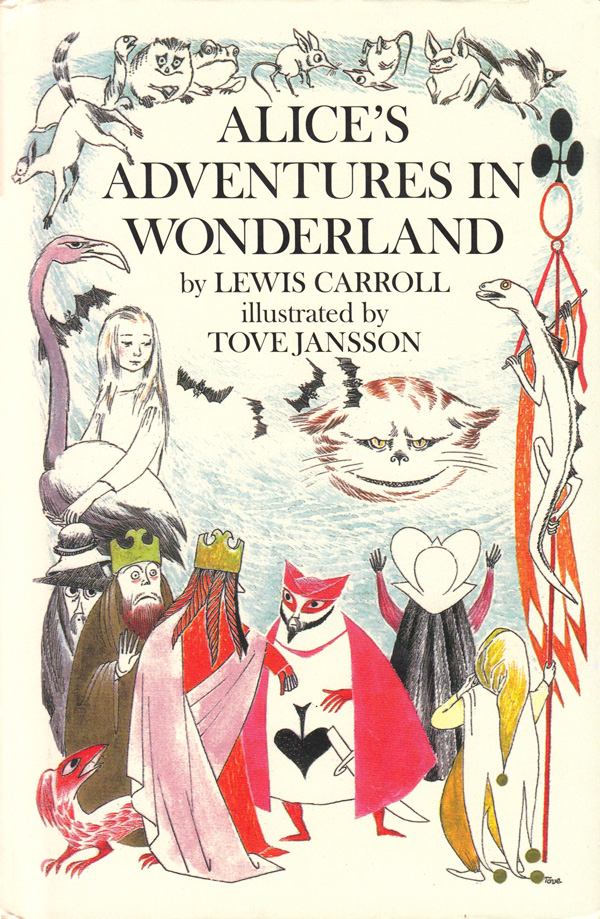

Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland remains one of my all-time favorite books, largely because Carroll taps his training as a logician to imbue the whimsical story with an allegorical dimension that blends the poetic with the philosophical. To wit: The Red Queen remembers the future instead of the past – an absurd proposition so long as we think of time as linear and memory as beholden to the past, and yet a prescient one given how quantum physics (coincidentally, a perfect allegorical exploration of Wonderland) conceives of time and what modern cognitive science tells us about how elastic our experience of time is. As it turns out, the Red Queen is far more representative of how human memory actually works than we dare believe.

Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland remains one of my all-time favorite books, largely because Carroll taps his training as a logician to imbue the whimsical story with an allegorical dimension that blends the poetic with the philosophical. To wit: The Red Queen remembers the future instead of the past – an absurd proposition so long as we think of time as linear and memory as beholden to the past, and yet a prescient one given how quantum physics (coincidentally, a perfect allegorical exploration of Wonderland) conceives of time and what modern cognitive science tells us about how elastic our experience of time is. As it turns out, the Red Queen is far more representative of how human memory actually works than we dare believe.

Illustration from Alice in Wonderland by Lisbeth Zwerger

"To be human," writes Dan Falk in In Search of Time: The History, Physics, and Philosophy of Time (public library), "is to be aware of the passage of time; no concept lies closer to the core of our consciousness" – something evidenced by our millennia-old quest to map this invisible dimension. One of the most remarkable and evolutionarily essential elements of experiencing time through human consciousness is something psychologists and cognitive scientists call mental time travel – a potent bi-directional projection that combines episodic memory, which allows us to draw on our autobiographical experience and call up events, experiences, and emotions that occurred in the past, with the ability to imagine and anticipate future events. Falk puts it unambiguously:

Without it, there would be no planning, no building, no culture; without an imagined picture of the future, our civilization would not exist.

Without it, there would be no planning, no building, no culture; without an imagined picture of the future, our civilization would not exist.

As it turns out, episodic memory – a term coined in the early 1970s by Canadian neuroscientist Endel Tulving, author of the seminal book Elements of Episodic Memory – is central to our capacity for mental time travel and, according to many scientists, fairly unique to humans. Unlike other facets of memory, such as the acquisition of new skills, which are rooted in the here-and-now, Falk points out that episodic memory allows us "to peer back across time, using our imagination to revisit just about any event that we choose." This mental reliving of the past may be the root of some distinct human maladies – take the wistful reminiscence over a lost love, for instance – but it is also central to our evolutionary survival, allowing us to anticipate future outcomes based on past ones and thus to plan better and be more prepared for what tomorrow may bring. (The dark side of this evolutionarily beneficial faculty is that our over-planning often ends up shortchanging our happiness.)

And yet the benefits outweigh the costs, in evolutionary terms. Falk explains:

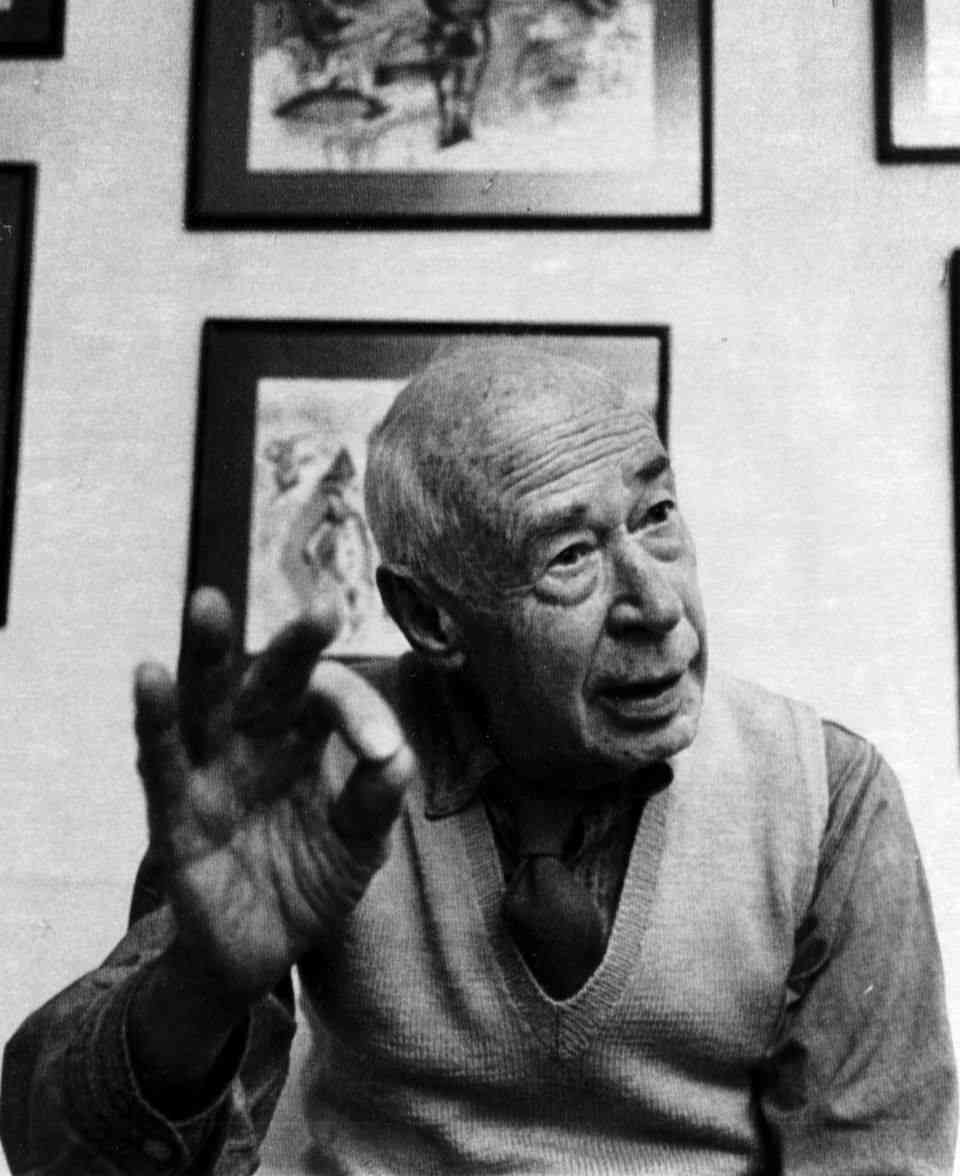

The capacity for mental time travel gave our ancestors an invaluable edge in the struggle for survival. They believe there is a profound link between remembering the past and imagining the future. The very act of remembering, they argue, gives one the "raw material" needed to construct plausible scenarios of future events and act accordingly. Mental time travel "provides increased behavioral flexibility to act in the present to increase future survival chances." If this argument is correct, then mental time travel into the past – remembering – "is subsidiary to our ability to imagine future scenarios." Tulving agrees: "What is the benefit of knowing what has happened in the past? Why do you care? The importance is that you've learned a lesson," he says. "Perhaps the evolutionary advantage has to do with the future rather than the past."

The capacity for mental time travel gave our ancestors an invaluable edge in the struggle for survival. They believe there is a profound link between remembering the past and imagining the future. The very act of remembering, they argue, gives one the "raw material" needed to construct plausible scenarios of future events and act accordingly. Mental time travel "provides increased behavioral flexibility to act in the present to increase future survival chances." If this argument is correct, then mental time travel into the past – remembering – "is subsidiary to our ability to imagine future scenarios." Tulving agrees: "What is the benefit of knowing what has happened in the past? Why do you care? The importance is that you've learned a lesson," he says. "Perhaps the evolutionary advantage has to do with the future rather than the past."

Modern neuroscience appears to confirm that line of reasoning: as far as your brain is concerned, the act of remembering is indeed very similar to the act of imagining the future.

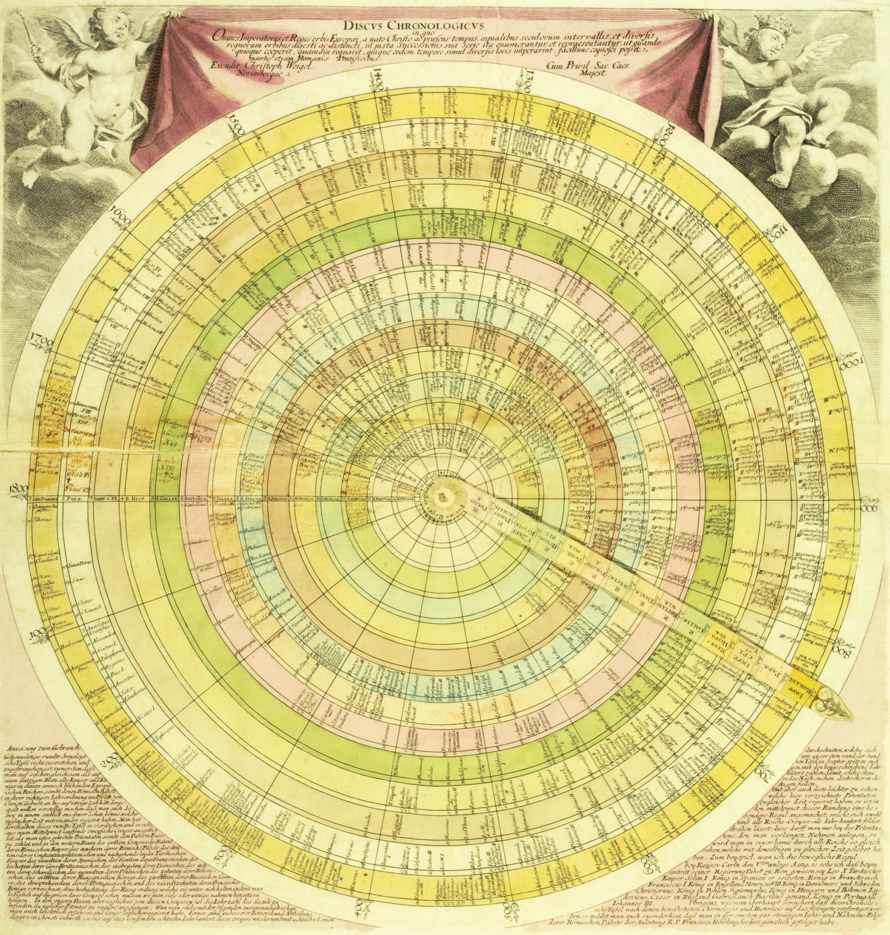

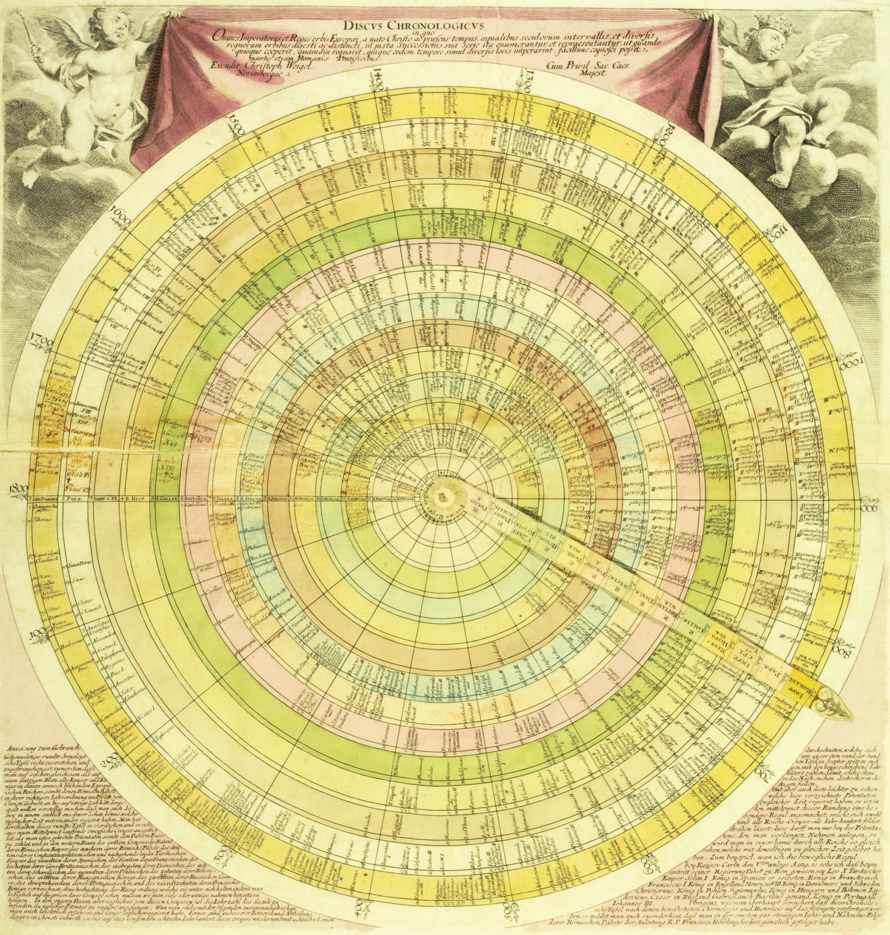

Discus chronologicus, a depiction of time by German engraver Christoph Weigel, published in the early 1720s; from Cartographies of Time

Though we might not be able to "remember" the future, as the Red Queen does, we do envision it in ways strikingly similar to how we picture events from the past – Falk notes that fMRI studies indicate we use similar regions in the brain's frontal and temporal lobes when thinking about events in either direction of time. What's more, psychologists have found that much like it's harder for us to remember an event in the distant past than a recent one, it's harder for us to imagine an event in the distant future than one expected to take place soon. This hints at the massively misguided way in which we think of and evaluate memory, which we falsely depict as a recording device, versus foresight. Falk writes:

When we imagine the future, we know what we picture is really just an educated guess; we may be right in the broad brushstrokes, but we are almost certainly wrong in the details. We hold memory to a higher standard. We feel – most of the time – that our memories are more than guesses, that they reflect what really happened. When confronted with a conflicting account of how last week's party unfolded, we cling to our beliefs: He must be mistaken; I know what I saw.

When we imagine the future, we know what we picture is really just an educated guess; we may be right in the broad brushstrokes, but we are almost certainly wrong in the details. We hold memory to a higher standard. We feel – most of the time – that our memories are more than guesses, that they reflect what really happened. When confronted with a conflicting account of how last week's party unfolded, we cling to our beliefs: He must be mistaken; I know what I saw.

Falk cites the Harvard psychologist Daniel Schacter:

[The brain is] a fundamentally prospective organ that is designed to use information from the past and the present to generate predictions about the future. Memory can be thought of as a tool used by the prospective brain to generate simulations of possible future events… We tend to think of memory as having primarily to do with the past… And maybe one reason we have it is so that we can have a warm feeling when we reminisce, and so on. But I think the thing that has been neglected is its role in allowing us to predict and simulate the future.

[The brain is] a fundamentally prospective organ that is designed to use information from the past and the present to generate predictions about the future. Memory can be thought of as a tool used by the prospective brain to generate simulations of possible future events… We tend to think of memory as having primarily to do with the past… And maybe one reason we have it is so that we can have a warm feeling when we reminisce, and so on. But I think the thing that has been neglected is its role in allowing us to predict and simulate the future.

Artwork by Andy Goldsworthy from his project Time

In order to mentally time-travel into the future, the brain has to accomplish a couple of things at once – we activate our "semantic memory," which encompasses our basic knowledge of facts about the world and thus helps paint a backdrop for the imagined scene, and we call on our episodic memory, which pulls on our autobiographical library of remembered experiences to fill in specific details for this general scene. Curiously, episodic memory tends to be rather flawed but, according to two scientists Falk quotes, that's okay since its core purpose is to provide "a more general toolbox that allowed us to escape from the present and develop foresight, and perhaps create a sense of personal identity."

To be sure, just like elsewhere in cognitive science, human exceptionalism may be misplaced here – scientists have found that other species are also capable of varying degrees of mental time travel. Falk cites one of the most intriguing experiments, involving scrub jays. He writes:

Psychologist Nicola Clayton and her colleagues housed the birds on alternate days in two different compartments – one in which the jays always received "breakfast," and one in which they did not. Then the birds were unexpectedly given extra food in the evening, at a location where they could access either compartment. The jays promptly cached their surplus – and they preferentially cached it in the "no breakfast" compartment. Because the birds were not hungry at the time of the caching, the researchers claim that the birds truly anticipated the hunger they would experience the next morning.

Psychologist Nicola Clayton and her colleagues housed the birds on alternate days in two different compartments – one in which the jays always received "breakfast," and one in which they did not. Then the birds were unexpectedly given extra food in the evening, at a location where they could access either compartment. The jays promptly cached their surplus – and they preferentially cached it in the "no breakfast" compartment. Because the birds were not hungry at the time of the caching, the researchers claim that the birds truly anticipated the hunger they would experience the next morning.

Still, the fact that humans are capable of remarkably elaborate and detailed mental time travel reveals something unique about our evolution and the development of such hallmarks of humanity as language and theory of mind. Falk writes:

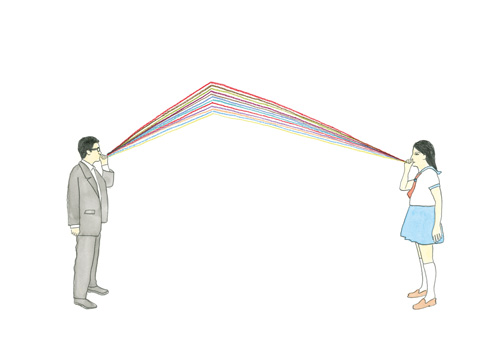

In all likelihood, the capacity for mental time travel did not develop in isolation but rather alongside other crucial cognitive abilities. "To entertain a future event one needs some kind of imagination," [the prominent psychologists Thomas] Suddendorf and [Michael] Corballis write, "some kind of representational space in our mind for the imaginary performance." Language could also play an important role. Our language skills embrace mental time travel by the use of tenses and recursive thinking; when we say "A year from now, he will have retired," we're imagining a future time in which some event – which has not yet happened – will lie in the past… Mental time travel may have been "a pre-requisite to the evolution of language itself." If mental time travel is indeed unique to humans, it may help us understand why complex language is also, apparently, unique.

In all likelihood, the capacity for mental time travel did not develop in isolation but rather alongside other crucial cognitive abilities. "To entertain a future event one needs some kind of imagination," [the prominent psychologists Thomas] Suddendorf and [Michael] Corballis write, "some kind of representational space in our mind for the imaginary performance." Language could also play an important role. Our language skills embrace mental time travel by the use of tenses and recursive thinking; when we say "A year from now, he will have retired," we're imagining a future time in which some event – which has not yet happened – will lie in the past… Mental time travel may have been "a pre-requisite to the evolution of language itself." If mental time travel is indeed unique to humans, it may help us understand why complex language is also, apparently, unique.

In fact, the development of mental time travel may even be how the concept of time itself came into existence – according to Suddendorf and Corballis, our species emerged victorious in "an extraordinary evolutionary arms race" largely due to our growing capacity for foresight and sophisticated language, which not only gave us culture and "coordinated aggression" but also, for the first time in evolutionary history, enabled us to understand the concepts of "past" and "future." The mental reconstruction of what has been and the imagining of what could be, they argue, created the concept of time and enabled us to understand the continuity between the past and the future. Falk, once again, puts it succinctly:

Mental time travel may indeed be the cognitive rudder that allows our brains to navigate the river of time.

Mental time travel may indeed be the cognitive rudder that allows our brains to navigate the river of time.

In Search of Time is a fantastic read in its entirety, covering such facets of life's most intricate dimension as how the calendar was born, why illusion and reality aren't always so discernible from one another, and what the ultimate fate of the universe might be. Complement it with these seven excellent books on time and a fascinating read on how our memory works.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"You only are free when you realize you belong no place – you belong every place – no place at all," the late and great Maya Angelou told Bill Moyers in their extraordinary 1973 conversation.

"You only are free when you realize you belong no place – you belong every place – no place at all," the late and great Maya Angelou told Bill Moyers in their extraordinary 1973 conversation.

The theme of home and belonging is central to Angelou's work – to her spirit – and is also at the heart of her beautiful contribution to Ellyn Spragins's 2006 anthology What I Know Now: Letters to My Younger Self (public library), which also gave us Naomi Woolf's spectacular no-bullshit letter to her younger self.

Angelou writes:

Dear Marguerite,

Dear Marguerite,

You're itching to be on your own. You don't want anybody telling you what time you have to be in at night or how to raise your baby. You're going to leave your mother's big comfortable house and she won't stop you, because she knows you too well.

But listen to what she says:

When you walk out of my door, don't let anybody raise you – you've been raised.

You know right from wrong.

In every relationship you make, you'll have to show readiness to adjust and make adaptations.

Remember, you can always come home.

You will go home again when the world knocks you down – or when you fall down in full view of the world. But only for two or three weeks at a time. Your mother will pamper you and feed you your favorite meal of red beans and rice. You'll make a practice of going home so she can liberate you again – one of the greatest gifts, along with nurturing your courage, that she will give you.

Be courageous, but not foolhardy.

Walk proud as you are,

Maya

Two years later, in 2008, Angelou would revisit the theme of home and belonging in her breathtaking letters to the daughter she never had.

What I Know Now features more contributions by such extraordinary women as Madeleine Albright, Roz Chast, and Ingrid Newkirk. Complement this particular gem with Maya Angelou on identity and the meaning of life

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"Art is not a thing – it is a way," Elbert Hubbard wrote in 1908. But the question of what that way is, where exactly it leads, and how to best follow it is something artists have been grappling with since the dawn of recorded time and psychologists have spent decades trying to decode, outlining the stages of creativity, its essential conditions, and the best technique for producing ideas.

"Art is not a thing – it is a way," Elbert Hubbard wrote in 1908. But the question of what that way is, where exactly it leads, and how to best follow it is something artists have been grappling with since the dawn of recorded time and psychologists have spent decades trying to decode, outlining the stages of creativity, its essential conditions, and the best technique for producing ideas.

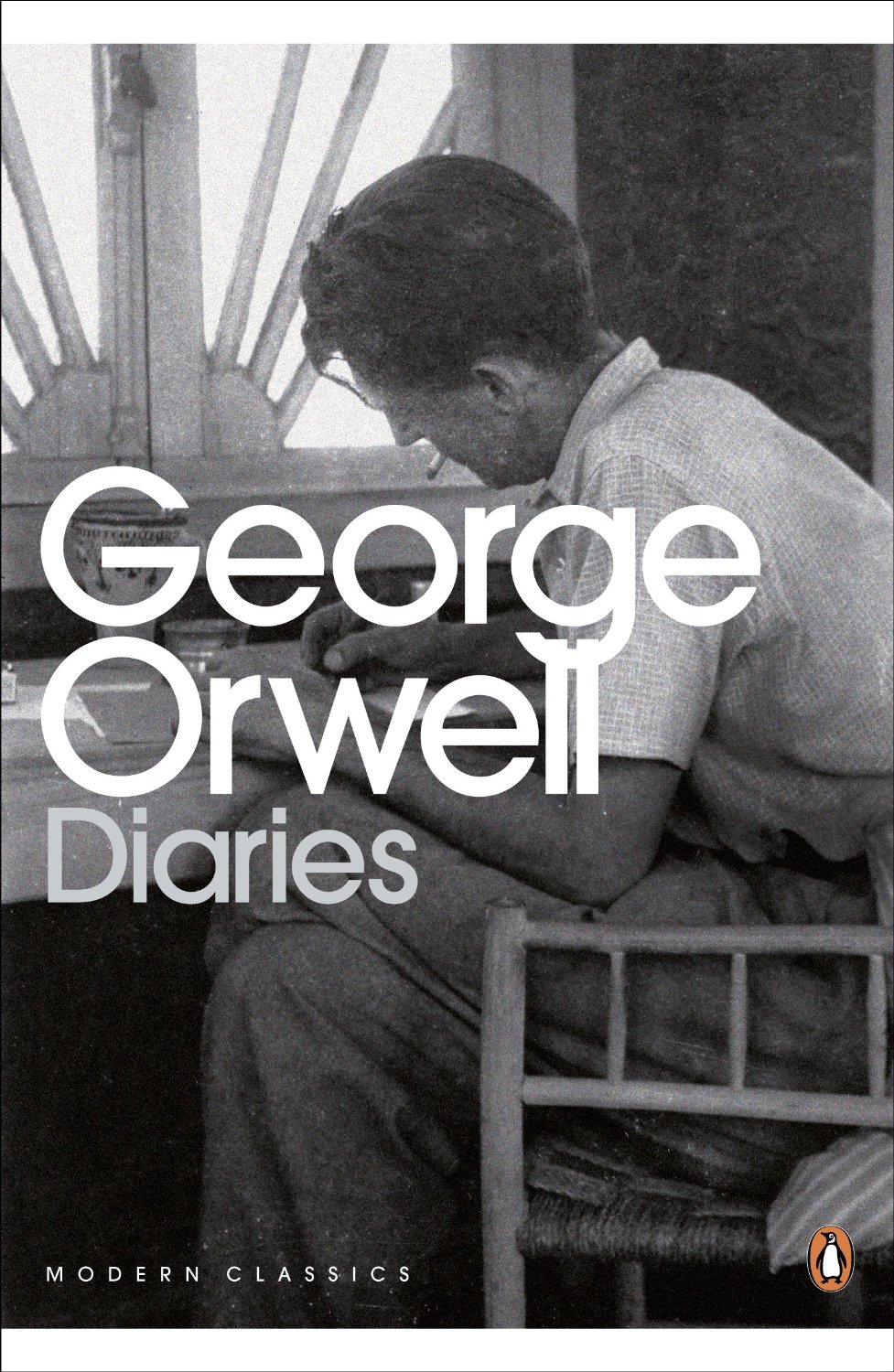

In 1978, a few months after she stopped drinking, artist, poet, playwright, novelist, filmmaker, composer, and journalist Julia Cameron began teaching artists – by the broadest possible definition – how to overcome creative block and get back on their feet after a "creative injury." What began as one-on-one lessons with a handful of artists became a larger workshop, then a course, which Cameron was invited to teach around the world, and eventually The Artist's Way (public library) – a seminal, much-beloved handbook on the creative life, exploring its gateways, its obstacles, and how we can get out of our own way. It's at once a practical set of techniques and a timeless philosophical meditation on the quintessential human impulse to create.

Art by Sydney Pink from Overcoming Creative Block

Writing in the introduction to the 10th anniversary edition, Cameron adds to the most beautiful definitions of art:

Art is a spiritual transaction. Artists are visionaries. We routinely practice a form of faith, seeing clearly and moving toward a creative goal that shimmers in the distance – often visible to us, but invisible to those around us. Difficult as it is to remember, it is our work that creates the market, not the market that creates our work. Art is an act of faith, and we practice practicing it.

Art is a spiritual transaction. Artists are visionaries. We routinely practice a form of faith, seeing clearly and moving toward a creative goal that shimmers in the distance – often visible to us, but invisible to those around us. Difficult as it is to remember, it is our work that creates the market, not the market that creates our work. Art is an act of faith, and we practice practicing it.

Indeed, while there is a strong spiritual overtone to the book that can feel off-putting to those of us skeptical of organized religion, Cameron takes care to invite the broadest possible definition of spirituality, echoing Flannery O'Connor and pointing out that it need not be one aligned with religion at all. She writes:

Think of it as an exercise in open-mindedness. . . . Remind yourself that to succeed in this course, no god concept is necessary. In fact, many of our commonly held god concepts get in the way. Do not allow semantics to become one more block for you. When the word God is used in these pages, you may substitute the thought good orderly direction or flow. What we are talking about is a creative energy. . . . There seems to be no need to name it unless that name is a useful shorthand for what you experience.

Think of it as an exercise in open-mindedness. . . . Remind yourself that to succeed in this course, no god concept is necessary. In fact, many of our commonly held god concepts get in the way. Do not allow semantics to become one more block for you. When the word God is used in these pages, you may substitute the thought good orderly direction or flow. What we are talking about is a creative energy. . . . There seems to be no need to name it unless that name is a useful shorthand for what you experience.

Art by Vladimir Radunsky from Mark Twain's Advice to Little Girls

That creative energy, Cameron argues, is part of our core nature. Rather than learning it, we simply need to unlearn all the techniques we've acquired for blocking it in the course of living our Serious Adult Lives. She writes:

No matter what your age or your life path, whether making art is your career or your hobby or your dream, it is not too late or too egotistical or too selfish or too silly to work on your creativity. . . . I have come to believe that creativity is our true nature, that blocks are an unnatural thwarting of a process at once as normal and as miraculous as the blossoming of a flower at the end of a slender green stem.

No matter what your age or your life path, whether making art is your career or your hobby or your dream, it is not too late or too egotistical or too selfish or too silly to work on your creativity. . . . I have come to believe that creativity is our true nature, that blocks are an unnatural thwarting of a process at once as normal and as miraculous as the blossoming of a flower at the end of a slender green stem.

Like T.S. Eliot, who extolled the mystical quality of creativity, Cameron recounts her own journey of learning to unblock that natural creative flow – the life-force Dylan Thomas memorably called "the force that through the green fuse drives the flower" – and considers the nonjudgmental mind necessary for true creative work:

I learned to turn my creativity over to the only god I could believe in, the god of creativity, I learned to get out of the way and let that creative force work through me… I learned to just show up at the page and write down what I heard. Writing became more like eavesdropping and less like inventing a nuclear bomb. It wasn't so tricky, and it didn't blow up on me anymore. I didn't have to be in the mood. I didn't have to take my emotional temperature to see if inspiration was pending. I simply wrote. No negotiations. Good, bad? None of my business. I wasn't doing it. By resigning as the self-conscious author, I wrote freely.

I learned to turn my creativity over to the only god I could believe in, the god of creativity, I learned to get out of the way and let that creative force work through me… I learned to just show up at the page and write down what I heard. Writing became more like eavesdropping and less like inventing a nuclear bomb. It wasn't so tricky, and it didn't blow up on me anymore. I didn't have to be in the mood. I didn't have to take my emotional temperature to see if inspiration was pending. I simply wrote. No negotiations. Good, bad? None of my business. I wasn't doing it. By resigning as the self-conscious author, I wrote freely.

This concept of surrender seems closer to Eastern philosophical teachings about the unity of the universe than it is to the Western notion of divinity in the religious sense. Cameron writes:

If you think of the universe as a vast electrical sea in which you are immersed and from which you are formed, opening to your creativity changes you from something bobbing in that sea to a more fully functioning, more conscious, more cooperative part of that ecosystem.

If you think of the universe as a vast electrical sea in which you are immersed and from which you are formed, opening to your creativity changes you from something bobbing in that sea to a more fully functioning, more conscious, more cooperative part of that ecosystem.

Art by Lisa Congdon from Whatever You Are, Be a Good One

And yet, with a hint of Wattsian distinction between belief and faith, Cameron makes a case for the "spiritual electricity" implicit to the creative process and writes:

The heart of creativity is an experience of the mystical union; the heart of the mystical union is an experience of creativity. . . . Creativity is an experience – to my eye, a spiritual experience. It does not matter which way you think of it: creativity leading to spirituality or spirituality leading to creativity. In fact, I do not make a distinction between the two. In the face of such experience, the whole question of belief is rendered obsolete. As Carl Jung answered the question of belief late in his life, "I don't believe; I know."

The heart of creativity is an experience of the mystical union; the heart of the mystical union is an experience of creativity. . . . Creativity is an experience – to my eye, a spiritual experience. It does not matter which way you think of it: creativity leading to spirituality or spirituality leading to creativity. In fact, I do not make a distinction between the two. In the face of such experience, the whole question of belief is rendered obsolete. As Carl Jung answered the question of belief late in his life, "I don't believe; I know."

This circular relationship between creativity and spirituality, Cameron argues, is paralleled by the techniques and practices of her "unblocking method." In a wonderfully reassuring passage, she writes of the "spiral path" toward creative recovery:

You will circle through some of the issues over and over, each time at a different level. There is no such thing as being done with an artistic life. Frustrations and rewards exist at all levels on the path. Our aim here is to find the trail, establish our footing, and begin the climb.

You will circle through some of the issues over and over, each time at a different level. There is no such thing as being done with an artistic life. Frustrations and rewards exist at all levels on the path. Our aim here is to find the trail, establish our footing, and begin the climb.

But despite the spiral nature of the path, Cameron draws on her extensive experience of working with artists to outline several stages of the creative recovery process – stages strikingly similar to those of grief, perhaps because the process itself necessitates that we let go of the attachments and psychoemotional habits that stand in the way of our contact with creative energy. Cameron writes:

While there is no quick fix for instant, pain-free creativity, creative recovery (or discovery) is a teachable, trackable spiritual process. Each of us is complex and highly individual, yet there are common recognizable denominators to the creative recovery process.

While there is no quick fix for instant, pain-free creativity, creative recovery (or discovery) is a teachable, trackable spiritual process. Each of us is complex and highly individual, yet there are common recognizable denominators to the creative recovery process.

Working with this process, I see a certain amount of defiance and giddiness in the first few weeks. This entry stage is followed closely by explosive anger in the course's midsection. The anger is followed by grief, then alternating waves of resistance and hope. This peaks-and-valleys phase of growth becomes a series of expansions and contractions, a birthing process in which students experience intense elation and defensive skepticism.

This choppy growth phase is followed by a strong urge to abandon the process and return to life as we know it. In other words, a bargaining period. People are often tempted to abandon the course at this point. I call this a creative U-turn. Re-commitment to the process next triggers the free-fall of a major ego surrender. Following this, the final phase of the course is characterized by a new sense of self marked by increased autonomy, resilience, expectancy, and excitement—as well as by the capacity to make and execute concrete creative plans.

If this sounds like a lot of emotional tumult, it is. When we engage in a creativity recovery, we enter into a withdrawal process from life as we know it. Withdrawal is another way of saying detachment or nonattachment, which is emblematic of consistent work with any meditation practice.

Illustration by Lisbeth Zwerger for Alice in Wonderland

But Cameron's most salient and empowering point is about the direction of the withdrawal:

We ourselves are the substance we withdraw to, not from, as we pull our overextended and misplaced creative energy back into our own core.

We ourselves are the substance we withdraw to, not from, as we pull our overextended and misplaced creative energy back into our own core.

What stands between us and that return to our core is the chronic perfectionism against which Anne Lamott so eloquently admonished. Cameron writes:

We are victims of our own internalized perfectionist, a nasty internal and eternal critic, the Censor, who resides in our (left) brain and keeps up a constant stream of subversive remarks that are often disguised as the truth. . . . Make this a rule: always remember that your Censor's negative opinions are not the truth. This takes practice. By spilling out of bed and straight onto the page every morning, you learn to evade the Censor.

We are victims of our own internalized perfectionist, a nasty internal and eternal critic, the Censor, who resides in our (left) brain and keeps up a constant stream of subversive remarks that are often disguised as the truth. . . . Make this a rule: always remember that your Censor's negative opinions are not the truth. This takes practice. By spilling out of bed and straight onto the page every morning, you learn to evade the Censor.

In the remainder of The Artist's Way, Cameron becomes the trusted sherpa on "an intensive, guided encounter with your own creativity – your private villains, champions, wishes, fears, dreams, hopes, and triumphs" – the kind of experience that will "make you excited, depressed, angry, afraid, joyous, hopeful, and, ultimately, more free." Complement it with Lamott's indispensable Bird by Bird, Neil Gaiman on making great art, and Anna Deavere Smith on what creative confidence really means.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, please consider helping with a small donation.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how our minds actually affect our bodies, 7 life-learnings from 7 years of Brain Pickings illustrated, Malcolm Gladwell on criticism and changing your mind, Bill Hicks on what freedom of speech really means, how to live with presence and break the tyranny of productivity, and more. – you can catch up

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how our minds actually affect our bodies, 7 life-learnings from 7 years of Brain Pickings illustrated, Malcolm Gladwell on criticism and changing your mind, Bill Hicks on what freedom of speech really means, how to live with presence and break the tyranny of productivity, and more. – you can catch up

No comments:

Post a Comment